Stephen Sondheim is no different. In Sweeney Todd: the Demon Barber of Fleet Street, his challenge was to see how many ways he could employ a four-note motive borrowed from an ancient dirge.

The Requiem Mass of the Catholic Church, or "Mass for the Dead", begins with the "Dies Irae", a centuries-old hymn depicting the Judgement day. Here is the first line, rendered in modern notation:

|

| The Grim Reaper |

Now here's what you may never have realized about Sweeney Todd:

Virtually the entire score, from beginning to end, is infused with and dominated by the Dies Irae. It's everywhere. This might come as a shock, since many of the quotations are so subtle that you'd never recognize them even on repeated hearings. But they're there, and it's pretty appropriate when you stop to consider the manner in which death drives the story.

On the one hand, it might sound tedious, repetitious and gloomy to have multiple musical numbers based on the first 4 or 5 notes of the Dies Irae; you might fear that the music would be too academic in nature for a compelling show.

You'd be wrong.

When composers limit themselves; that is, when they set up restrictions in their musical materials ("Rule: you must find ways to use the beginning of the Dies Irae"). it brings out their best in terms of imagination and resourcefulness. Here's a summary of the various ways Sondheim, a genius, manipulates these seemingly unpromising four notes.

- Right away in "The Ballad of Sweeney Todd", which is the prologue before Act 1, the chorus literally screams the motive following the first two stanzas:

- When we first meet Mrs. Lovett, she strikes us as an eccentric but likeable old busybody; we will only gradually come to realize what a psychopath she is. But in her first solo, the music gives us a clue. On close examination, the notes below on the words "What's your hurry?" are an upside-down version of the Dies Irae.

- When Lovett presents Sweeney with his old set of razors, he croons an ecstatic love song to them. The very first four notes are an exact mirror image of the Dies Irae. Notice how the hymn-tune them climbs higher and higher vocally, corresponding to the scheme for vengeance that is now rising in his mind as he sings. The vocal line illustrates how he's thinking: Death is rising for Judge Turpin!

- When we meet Todd's daughter Joanna, who would be the ingenue in a more conventional musical, her entrance aria "Green Finch and Linnet Bird" has a particularly ingenious manipulation of Dies Irae. The musical death-tune is hidden in the middle of her vocal line in its original form (with a passing-tone inserted between the two syllables of "Irae"). And, with great song-writing craft, it appears when the girl mentions "Night"ingale and "Black"bird:

- In the scene of Sweeney's shaving contest with "The Great Pirelli", the latter's simple young assistant Toby acts like a carnival barker, drawing a crowd with his sales pitch. Here the back-and-forth oscillation in his patter is generated by the first three notes of Dies Irae. The original form of the D.I. occurs in the third bar:

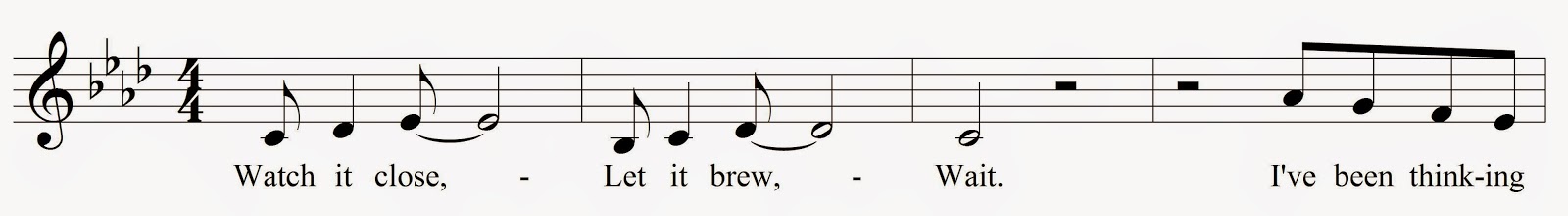

- Lovett sings a near-lullaby to Todd when he grows impatient for Turpin to visit his shop in her sly solo "Wait". Here Sondheim is particularly subtle in introducing the Dies Irae; rather than appearing note-to-note, it's the first note of each bar in this excerpt that reveals the tune, allowing for octave transposition on the word "I've":

- Meanwhile, young Joanna, a most neurotic young lady (with good reason), is making plans with Anthony to elope. In expressing her disgust over Judge Turpin's attentions, she invokes half-serious plans of suicide. Sound like a good opportunity for the Dies Irae? Our fave tune is quoted neatly and on point on the words "I'd rather die":

- When Turpin makes his angry exit, the frustrated Sweeney erupts in over-the-top musical rage ("Epiphany"). While the low brass in the orchestra snarl out the Dies Irae underneath him,

Sweeney is growling a vocal line with an inverted Dies Irae on the words "Mrs. Lovett":

- The witty "A Little Priest" duet for Todd and Lovett reprises the Dies Irae version heard in "Worst Pies", and the Act 2 curtain-raiser "God That's Good" allows Toby to repeat his own D.I., simply substituting pie-centric lyrics in place of elixir rhymes. The next occurrence of note is in Lovett's vacation fantasy "By The Sea", in which the tell-tale oscillation in the opening phrase is the unmistakable sign of the Dies Irae. Here an inverted example is seen on the words "that's the life I covet", with one extra note inserted on "I":

- This post is getting long, so I'll give you one more example, though there are others. When Toby, who is somewhat related to the Fool of Shakespearean times, naively offers to protect Lovett from Todd; his tragedy is that he senses evil in the latter but not in the former. The Dies Irae chooses the most apt moment to appear, on the words "Demons are prowling":

Bottom line: the score to Sweeney Todd is so saturated with the Dies Irae that it's as if Death itself was a character; a character who, rather than have a solo number to sing, instead inhabits the music of the human players.

Tedious, repetitious and gloomy? Hardly. In the hands of a master craftsman like Sondheim, the four-notes of the Dies Irae are like a musical chameleon; a "tune of 1000 faces", so to speak. Conveying every affect from bawdy humor to girlish impetuousness to rage to filial love, the Dies Irae lets us know that the Grim Reaper is never far from these doomed (but entertaining!) citizens of London.

This is brilliant! I'm pretty sure I've heard it in Act III of Fanciulla too--just briefly, when Jack Rance is gloating over the capture of Dick Johnson.

ReplyDeleteOne of your best pre-performance talks lat night at George Mason. My wife and I had seen "Sweeney Todd" twice on stage and once on the screen, and never picked up on ANY of this.

ReplyDeleteOf course, since she's not familiar with "Parsifal," we're going to have to dig out my recording...