|

| Sheesh - even GUM can have a dual nature! |

The dual nature we all exhibit if we live long enough in this troubled and troubling world.

With one exception (an exception explained by a line of recitative), every character in Sweeney Todd is two characters - just like me. And you. "We all deserve to die", Todd bellows in his volcanic solo "Epiphany". That assertion is debatable, but it is true that all of us have aspects of ourselves we display to the world, and other aspects we prefer no one know about.

In Sweeney Todd, even the chorus has two identities. Beginning with the Prologue ("The ballad of Sweeney Todd"), we see them functioning as a Greek chorus, singing commentary on the action as a single unit. Yet at other times they splinter into highly individualized townspeople of London; this one skeptical of Pirelli's elixir, that one buying a bottle.

Of course, The Great Pirelli himself is one of the obvious case-studies in duality. In public, he's babbling in a Chico Marxian "Eye-talian" patois. Privately, he's the Irishman Daniel O'Higgins.

The opening scene of Act I offers a subtle bit of duality. Anthony Hope launches the music with a jaunty song in praise of London, a solo guillotined by Sweeney's impatient interjection. Within a few minutes Todd repeats the opening of "No place like London", but in place of Anthony's youthful gushing optimism, now the words "There's no place like London" carry the weight of the barber's bitter cynicism.

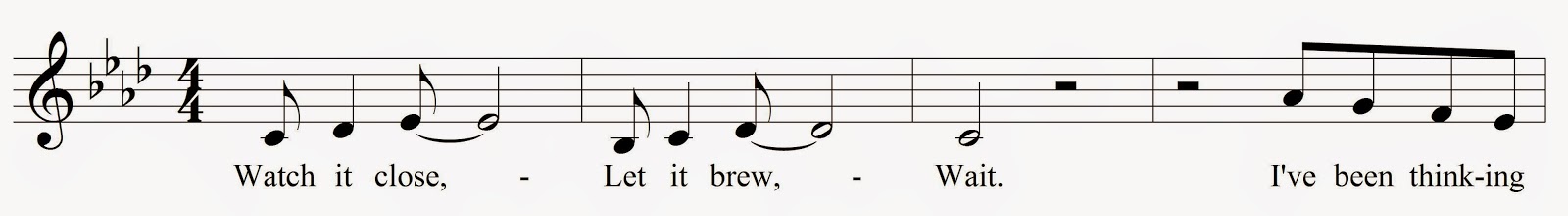

Even songs can have a dual nature in this work.

That opening scene also introduces us to the Beggar Woman, a figure whose duality has duality! Long before it's confirmed that this deranged homeless creature is Todd's wife Lucy (duality #1), she is depicted flipping randomly between two mental states: now whimpering pitiably, now spewing obscene propositions to the two men.

How about Anthony? Doesn't he ruin my theory? After all, he's pretty much the same "golly-gee whiz" paragon of earnest good will at the end as at his first entrance.

Ah, but Sweeney himself offers the explanation for his lack of duality. "You are young," he sings gravely, "Life has been kind to you. You will learn."

As for Johanna, Anthony's love and Todd's child, in a conventional musical or operetta she would be the ingenue: sweet, young, innocent and endearing.

Hmmm. Well, three out of four ain't bad.

Johanna is damaged; life has not "been kind to her". The ward of Judge Turpin, a prisoner in his house and the current object of his perverse desires, she is agitated to the point of neurosis. It is Johanna who proves capable of violence in the scene of Fogg's Asylum, grabbing the pistol from her lover and shooting a man in cold blood. Yet, at the same time, the audience does find her endearingly charming as well.

One might speculate, as Johanna's neuroses develop and life stops treating Anthony with "kindness", that their fate may eventually be as bleak as that of the rest of the characters.

Of course, our title character, his partner in crime Mrs. Lovett, and his adversary all support the theme of man's duality. Like his former apprentice O'Higgins, Todd has two names. He is Benjamin Barker, an honest tradesman, devoted husband and loving father. He is Sweeney Todd, insane serial murderer.

Sondheim is careful to depict Todd's duality in musical terms as well. In the aforementioned "Epiphany", the music careens crazily from short rhythmic bursts of staccato rage (Who sir? You, sir? No one in the chair, come on!") to long, anguished, unrhymed wails of grief ("And I'll never see Johanna, no, I'll never hug my girl to me").

As for Mrs. Lovett, this one shouldn't even require explanation. She's a chatty scatterbrain. She's a heartless psychopath. When Todd ignores her shy confessions of love in "My Friends" in Act I, Sondheim tricks us into feeling sorry for her in the face of his disregard. But by the time she sings "By the sea" in Act II, we know better, even though Todd continues to ignore her; we've learned that she's the worse monster.

And Turpin fits the mold as well. A distinguished jurist to his neighbors, only Johanna, Todd and Anthony see the persona of sexual deviate he hides from the world. Even his henchman Beadle Bamford alternates from being a responsible community activist ("Glad as always to oblige my friends and neighbors") to enabling Turpin's brutality with brutality of his own.

Finally, even Tobias, the most tragic figure in the piece, will show us two personas. The treachery of Mrs. Lovett will trigger his metamorphosis from good-hearted simplicity (with a dark head of hair) to babbling Avenging Angel with hair shocked white.

You and I are no different, of course. There are aspects of my own nature I keep hidden from the world, and the same is true of you, Faithful Reader. Let's confide in one another, shall we? Let's confess our darker natures! It'll be fun!

You go first.